Quantum CFD for realistic geometries of obstacles

From wind-turbine blades to jet engines, unwanted aerodynamic noise reduces efficiency, increases fuel burn, and is subject to regulatory limits. Engineers address these issues using computational fluid dynamics (CFD), which is the numerical solution of partial differential equations (PDEs) on a spatial grid that describes how pressure and velocity evolve in a flowing gas. CFD is everywhere — in aerospace, automotive, energy, climate research, and even consumer-electronics cooling — but it is notoriously expensive. Each increase in spatial resolution dramatically increases both the required memory and the run time. For high-fidelity aero-acoustic simulations, the computational grids easily require billions of points, which challenges even the largest HPC clusters.

If you're exploring quantum-ready simulations beyond classical HPC limits, Haiqu can help you evaluate what’s possible today and what’s coming next.

The Quantum Leap

One of the recent approaches to solving the PDE itself is by mapping it to a quantum system evolving under a Hamiltonian, which can very naturally be simulated on a quantum computer. However, in order to apply to realistic problems, such as sound scattering from an aircraft wing, the appropriate fluid equations and boundary conditions that describe arbitrary geometries and obstacles must be included in the quantum Hamiltonian, which is highly nontrivial.

This is precisely the problem that the Haiqu researchers addressed in their work, “Quantum Hamiltonian simulation of linearised Euler equations in complex geometries”. They showed how classical CFD equations for sound propagation can be directly mapped to a quantum computation, particularly when including complex obstacles (like wings!), in a way which preserves the exponential advantage of the quantum approach.

Turning Everyday Air Flow into a Quantum Algorithm

The air particles behave according to three simple bookkeeping rules: mass is never lost, momentum changes only when forces act, and energy has to go somewhere (it cannot appear or vanish). Writing those ideas down for every tiny parcel of air gives a system of linked equations—one for each rule—so that changes in pressure, density, and velocity stay consistent everywhere in the flow. For real-world viscous fluids, these equations are the famous Navier–Stokes equations.

To simplify the problem, we use the approximation that air is an inviscid fluid (no stickiness) and does not exchange heat. Under those two assumptions, the Navier–Stokes equations collapse into the much simpler Euler equations. Imagine now a smooth and uniform background flow of a fluid - picture a steady breeze moving in a single direction. The sound waves we care about are tiny ripples on top of that steady breeze, and we can therefore linearise the Euler equations: keep only the terms that describe these small disturbances and drop all higher-order contributions.

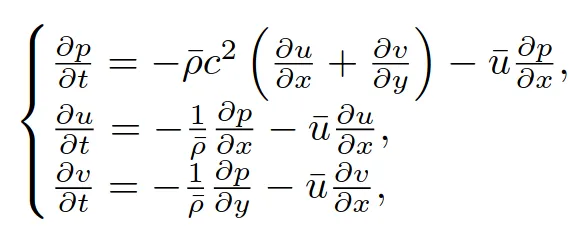

The linearised Euler (LE) equations so obtained (here: in two dimensions) describe how pressure and fluid velocity components evolve while being carried downstream by the uniform flow with speed u in x direction:

Above, u,v,p denote, respectively, the velocities in the x,y directions and the pressure deviation from the average, while is the density of the environment, and c is the speed of the sound.

As sound is a pressure wave, the LE equations model the propagation of noise through the air. In the absence of background flow (u=0) they reduce to a simple wave equation.

We can generally write our classical PDE system as df/dt=Af with f=(p,u,v), for a linear operator A. Interestingly, when A has certain properties — in particular, when it is made up of real numbers and is antisymmetric — we can rewrite this problem in a way that looks just like how quantum systems evolve. In quantum physics, the evolution of a system over time is described by the Schrödinger equation df/dt=-iHf, which depends on the Hamiltonian operator H. You can think of the Hamiltonian as the "energy operator", it prescribes how the system behaves, controlling its evolution. If we can rewrite our classical problem in terms of a Hamiltonian — by formally setting H=iA (where i is the square root of -1) — then solving the original problem becomes like simulating a quantum system over time. As Hamiltonian operators obey certain mathematical properties (hermiticity), such rewriting is only sometimes possible, and depends on the details not only of the equation, but also of the boundary conditions, all of which determine the structure of the matrix A.

Haiqu researchers have shown how this can be achieved for the linearized Euler equations, even when arbitrarily complex boundary conditions, describing obstacles such as wings, pipes, constructions etc. are included. This allows modeling aero-acoustic phenomena in realistic scenarios. Since the ultimate goal is the simulations of these systems on real quantum devices, an important contribution of the work is the detailed construction of explicit quantum circuits, which can be executed on typical QPU architectures, for example superconducting devices.

Figure 1 - Ideal quantum simulation of the quantum circuits derived by Haiqu for the 2D pressure wave propagation on a constant background flow in the x direction with an impenetrable obstacle (colored in darkgreen). One can observe how the wave, starting from a single point source, propagates and moves with the flow, bending the object and reflecting from it.

That is, including obstacles in the flow does not lead to an asymptotically higher computational cost or increase the simulation error.

From Research to Real Quantum CFD

Haiqu researchers have developed a novel quantum algorithm for simulating the linearized Euler equations. The approach demonstrates a clear potential for quantum advantage by leveraging exponential grid encoding with only polynomial quantum resources, and allows to construct simulations of real-world aero-acoustic problems, thanks to an efficient implementation of complex obstacles and boundary conditions in the equation.

Move from insight to execution. See how Haiqu turns quantum CFD research into runnable workflows on today’s quantum hardware.

Download our research paper below for more information.

Interested in more Quantum CFD research? Explore the AWS blog post about our work with Quanscient on running the largest-grid Quantum CFD simulation on a real QPU, as finalists in the Airbus & BMW quantum challenge.